This proprietary label stemmed primarily, I believed, from a place of love and caring. So dedicated was I to my chosen profession, that it just sort of slipped out whenever I was sharing a funny anecdote from -- or telling about a lesson that had transpired in -- my classroom.

Residential Schools

Of particular horrific fascination for me has been the unearthing of grisly facts about the Residential School System in Canada, a system through which the government of Canada removed -- against their or their families' wills -- school-aged children from their homes, and sent them to overnight schools to unlearn their language, their culture, their identities (and often, to be victims of physical, sexual and/or emotional assault). This happened for several decades.

The inter-generational trauma that resulted is well documented, as the FNMI children which the primarily white Anglo-Saxon patriarchal government claimed as their own grew into a generation of young adults who had little to no understanding of who they were as parents, as indigenous Canadians, as human beings, even.

And those are the ones who survived the mass abduction.

Discrimination Against Children on Reserve

A close second topic of horrific interest for me has been the story of Cindy Blackstock and the "successful" court case against the federal government.

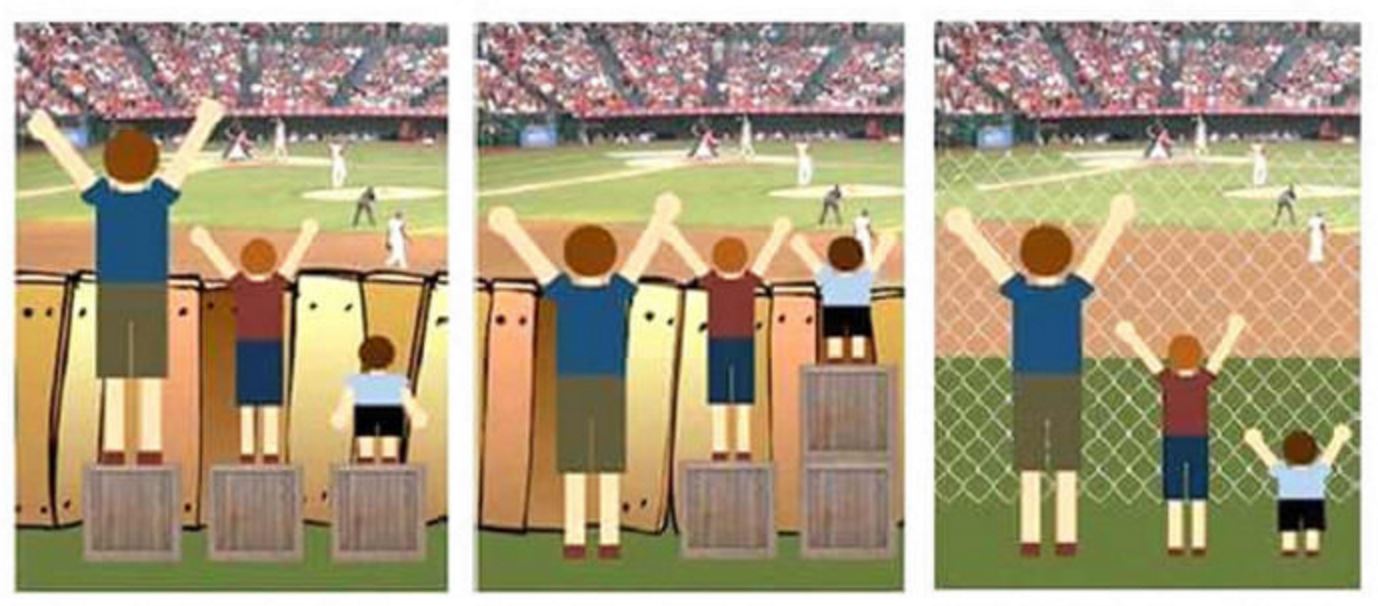

I write successful in quotation marks because even though after nearly a decade of struggle with the courts, the case claiming the government was systemically discriminating against children on reserve was finally heard, and a judge found the government guilty, children (and their families) living on reserve continue to experience a different (lower) level of child welfare service than their off-reserve counterparts.

Despite the issuing of a second compliance order by the courts!

(If you want to learn more about this story, check out the film, "We Can't Make the Same Mistake Twice", directed by the graceful yet powerful, 80-something-year-old Alanis Obomsawin, herself a survivor of the system.)

"Our Children"

These two lessons in particular have made me reflect on my own use of "my" when describing the children in my care as a classroom educator over the years.

Our director drew our attention to the use of the word "our".

An interesting discussion ensued with the team, about our intent in using the word, vs the possible perception by people for whom a government appropriation of children gone wrong was all too close in the collective memory.

Despite our aim in sharing the message that educating our province's children was a collective responsibility, a partnership that we should take very seriously, not underestimating their gifts, talents and competencies, I understood our Director's concern: In the Kantian sense here, impact outweighs intent, regardless of how benevolent that intent is!

"My" Kids

On my desk at work, I have many photos of children. The oldest is a class photo from my third year of teaching, when I had the great privilege of spending my days with students in Grades 1-8 who were learning English. The photo was taken on the steps of the Butterfly Conservatory in Niagara, on a cross-grade field trip I had convinced my principal at the time was absolutely necessary in order to build a sense of community amongst the often-ostracized members of our school's ESL population. Gazing in wonder at the butterflies surrounding them, the little ones sat obediently for the camera (their middle school counterparts were in a different section of the building at the time). On the bus ride home, most of them fell asleep in the laps of their older peers!

The second group photo on my desk is also from the early part of my career, a shot from picture day at school, this time a contained class of students in Grades 1-3, all of whom had been identified as having special learning needs. Not long after that photo was taken, one of the youngest students in the class came to me after having spent a few period in another classroom... she was perplexed: "Are we the only children who sit on balls?" she asked in bewilderment, referring to the class set of therapy balls the parents had purchased for me at the end of the previous school year, after seeing the positive impact of daily movement on their childrens' ability to focus. It had never dawned on the dear little sweetie that the students in other classes might sit on "normal" chairs! (As a quirky aside, I met a former classmate of hers, now in her 20s, in an Uberpool earlier this year.)

The third group of children that has been immortalized in a frame on my desk is perhaps the most unique: A group of no fewer than 9 sets of multiples (well, 8.5; one twin was home sick) -- with parental permission, I had invited a board photographer to the school to capture on camera the phenomenon of a twinning rate that was more than double the norm! The 18 of us crowded into my office (I was an acting VP at the time) to take the group shot that still sits on my desk 10 years later, and then the photographer took individual headshots of each twin, which we later made into a matching game; one went home with each kid, and a few copies stayed in the school library. (The missing twin was monozygotic, so we just took two photos of his brother!)

I recognize now that while each of children in these photos holds a special place in my heart, as do the many students I have taught since then, they are not "my" children. They are kids who were -- for a short time -- entrusted to my care by families who courageously sent them off to me and my colleagues. Sometimes we did a pretty good job of earning that obligatory trust. Other times, I have no doubt we let them down.

Alex and Simon

The only real photos of my kids on my desk are the ones of two little blond boys (sometimes mistaken for girls, due to the length of their locks).

One small yellow frame depicts a three-year-old painting at the kitchen table in the old house, his chubby fingers gripping the brush purposefully. A nearby frame of equal size (but in blue) shows his brother sitting at the outdoor dining table at a friend's cottage, a giant sausage he'll never eat on the plate in front of him.

An unframed print of one with the other in a headlock, visible through the open door of their playhouse on PEI sticks to the magnetic door of one of my cabinets. On another cabinet door, behold one photo of a boy standing while his brother insists on lying down on the ground near the lighthouse on the island's south shore. And then there are two small black and white shots from photo day at Simon and Alex's school in Toronto, taken a long time ago -- Grade 2, maybe?

The best of intentions aside, these are the photos of my real kids, the only children I have the right to claim publicly as my own. And even that is changing as they grow older and become more and more their own people, and less and less "my" children.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed