Integration Preamble: The Generalist

As an elementary school teacher I found integration of subject areas both delightful and necessary in my teaching, in order to “cover” the many curriculum documents I had to ultimately report on students' achievement of. With few rare exceptions, my elementary classroom teaching experience was that of a generalist rather than a specialist, and this meant that I would typically see one "main" group of students for most of the school day. This arrangement made it possible me to integrate quite easily.

A cross-curricular, integrative approach to teaching and learning allowed for pedagogical practice that was responsive to both student learning needs and interests, and also emerging hot topics in the media.

An example that springs readily to mind was the Syrian refugee inquiry my instructional coach and I facilitated my Grade 6s through when then-prime-ministerial candidate Justin Trudeau pledged to usher in a specified number of refugees by a certain date if elected. So many of my students that year came from the middle east, and so their interest to engage with this news topic was keen.

By examining the context of many refugees’ journeys from their homes, and their subsequent arrival in far away places like Canada, we expanded our vocabularies, increased our writing skills and commitment, explored math concepts like measurement and unit rate, and engaged with social studies curriculum expectations addressing the stories, contributions and systemic struggles of different people groups in Canada. By doing much of our research watching videos (many in Arabic with English subtitles) and using photos from news articles, my class and I were also able to attend to a number of media literacy expectations from the Language curriculum.

Teaching in this way has become second nature to me, and I find ways to differentiate assessment tools and opportunities in ways that meet the learning needs and leverage the affinities of my students, while still being grounded in criteria that we co-construct to meet our overarching learning goal(s). It’s an ever-evolving instructional design that is both equitable and robust.

The Specialist

My secondary colleagues, by contrast, often teach one specific course, allowing them the luxury of focusing on one subject.

Unencumbered by the need to report on 12 or more subject strands, they can and often do become experts in their field, zeroing in on the overall and specific expectations of the curriculum document that forms the foundation of their particular course.

Advance Notice

As I am discovering while working with my secondary colleagues, it is often considered best practice (and indeed, some schools or boards may have a policy that insists on this) to share a course outline, with specific assessment dates, with students at the outset of a course in high school.

Some course outlines even include the exact percentage each assignment and/or test will be worth.

The thinking is something along the lines of “by making sure students know ahead of time when and how they will be evaluated, we are giving everyone the same shot at getting good marks”.

Emerging Criteria

As is becoming more and more clear to me (both in my last few years as a classroom educator and in my current role as an Education Officer with the Ministry of Ed), the power of Assessment AS Learning can only really be harnessed effectively if students are heavily involved in co-constructing success criteria with their teachers, and if the teacher allows these criteria to emerge throughout a teaching and learning cycle.

While a teacher should certainly create and share a curriculum-based learning goal with his students at the outset of an inquiry or a unit of study, and would do well to have criteria in mind ahead of time, an authentic learning climate will engage students in such a way that the students feel they truly have at least some ownership in the classroom, and this ownership manifests itself very effectively when they can contribute to the co-creation and ongoing editing of success criteria to meet a learning goal throughout a course or unit of study.

Descriptive Feedback

If student learning is to improve according to the principles of Growing Success (our province's assessment policy), teacher, peer and self feedback must not only describe a student's progression towards an established learning goal as described by the criteria, but the student much also be allowed to act on this feedback to improve his performance and demonstrated achievement of said goal.

The Conundrum

From what I can see, and based on my experiences with the average learner, pre-communicating assessment (evaluation, really) dates and assignments inhibits a growth mindset stance to learning: Why would a student take seriously descriptive feedback throughout the learning cycle if in fact "it doesn't count" as part of their much-coveted final mark?

Gleaning a better understanding of the existing culture and practice in many secondary schools is helping me to appreciate the hurdles faced by my high school colleagues when they are prodded by assessment workshop keeners like me to be "responsive" in their assessment and instruction practices with students!

A Broader Understanding of Equity

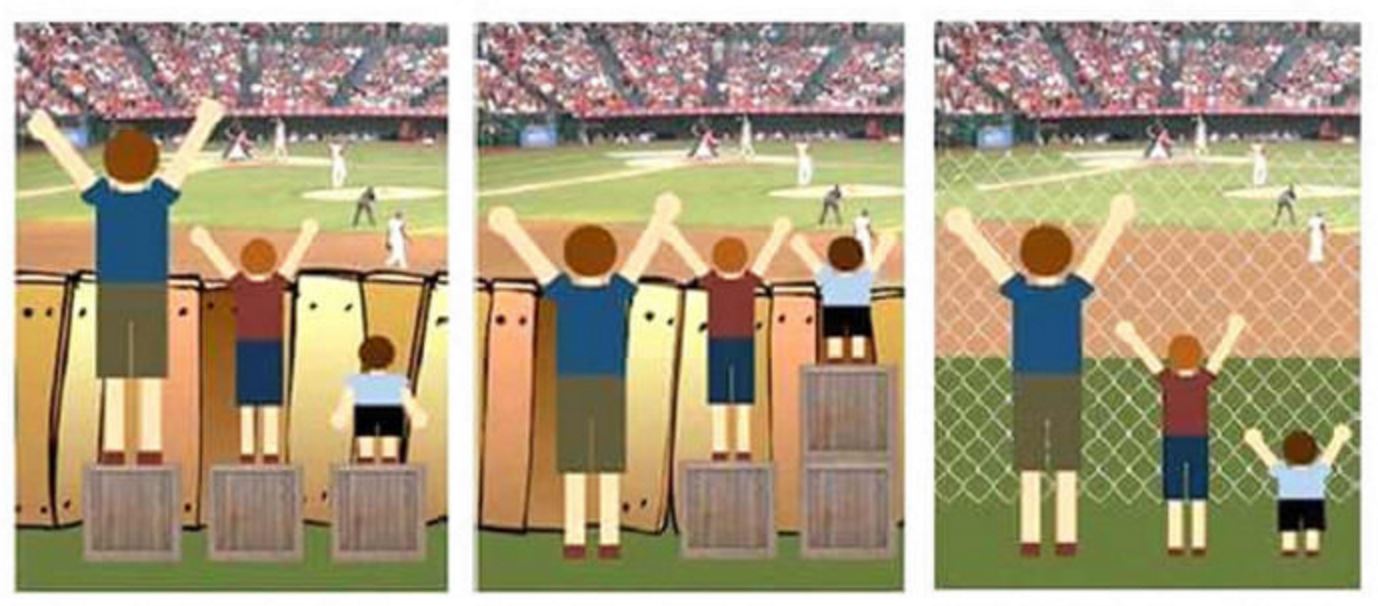

Communicating ahead of time with students about course expectations, assessment practices and the like are an important part of a "no surprises" equitable approaches diet for teachers and their students. However, I would argue that in order to use assessment for and as learning effectively, and establish -- as Growing Success calls it -- a climate that is "fair, transparent, and equitable for all students", we need to broaden our understanding of what it means to adopt an equity perspective when it comes to assessment.

Inviting students into the conversation about what a specific learning goal might look, sound and feel like when demonstrated by the learner is one piece of the puzzle. Allowing enough open-endedness in a course or class that criteria can be properly co-developed, refined and edited as needed, and that feedback based on said criteria can be given, received and applied throughout the learning cycle before a final grade is determined, is another important piece, and one that may require significant rethinking of how far in advance (if ever!) a course outline is etched in stone.

We can't change the world, says a particularly fatalistic-minded colleague of mine, but we can and should improve the world of those in our immediate sphere of influence.

I believe making the world a better place for the students in our care begins with an equity stance when it comes to learning and assessment. Lucky me in my job I am surrounded by deep thinkers and experienced educators who will have lots to say about this matter. I look forward to seeking their wisdom as I consider how best to preach the messages in Growing Success in ways that honour and respectively stretch (where required) the existing culture of secondary school educators.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed