A former secondary school history teacher had been asked to speak at a staff professional learning day. She and some colleagues were sharing details of a trip they had taken to a history site earlier in the year, and linking the experience to the concept of leadership. Her role was to set the historical context of the event.

As she spoke, we were riveted; all 200 people sat glued to her every word. The manner in which she presented made it clear that she was both an expert on the topic, and a passionate educator about said topic. She "lectured" in a way that engaged us far more deeply than I could probably sustain a group's interest on pretty much any subject (unless maybe when regaling my pre-service teacher candidates with classroom management stories from the field)!

This really made me begin to rethink the "must be a generalist" position I had held for so long. Perhaps, if ALL subject specialists were as knowledgeable and passionate about their topic as my colleague was about hers, AND assuming they were also good pedagogues (i.e. had a firm grasp of the assessment for learning models outlined in Growing Success, and understood UDL and DI principles and used them regularly in their practice), then maybe having subject specialists WAS the way to go.... ?

I puzzled over this for some time, as I still had a nagging feeling about it all.

Despite being able to take care of systems and structures like timetabling (to avoid having middle school students run across the school from class to class) and other things that typically bothered me about the specialist model, I still felt a real sense of loss when I thought about giving up the generalist model altogether.

Finally, it dawned on me: Achieving a high degree of expertise in a particular field necessarily precludes considerable knowledge in other fields. While becoming an expert in an area is important for some professions, in teaching, it can actually create barriers for our students. Where a good generalist can help learners uncover connections between subject areas, and can facilitate meta-cognitive growth by highlighting skills and competences that transcend a variety of areas, a subject specialist risks becoming a "one trick pony", from whom students may even learn only one perspective on an event or skill.

Being forced to reach across curricula as a generalist breeds new knowledge for not just the students, but more importantly, the teacher, who begins to see things from different perspectives, and may often be encouraged to reexamine her own long-held beliefs. (Less of a danger from the comfort of the subject specialty the specialist has always taught.)

But when you think in an integrated fashion, time flies!

I remember preparing a Science lesson, on flight, for that class... though really it was a lesson in dissecting non-fiction text... and also a digital and visual literacy lesson, as we had begun to experiment with mind maps. And all that while we focused on developing perseverance and task-commitment while working effectively with a partner.

Similarly, the year before, the students and I dug into the stats on carding, as we examined racial profiling through data management and probability. Was it a math lesson? A social studies lesson? A lesson in research and note-taking skills? A expository writing and debate lesson?

It was all of these.

Perhaps the answer is not generalist or specialist. Perhaps the answer lies in new systems and structures at both the elementary and secondary school levels, structures that allow for a small group of diverse educators to work together to support the learning needs of a group of students.

I imagine a system where -- rather than one teacher having responsibility for one class, and a few periphery teachers are enlisted to fill in gaps like french or phys. ed. -- instead 3-4 educators are collectively in charge of teaching all subjects to a group of 60-80 students. Ideally each educator team is carefully selected to include diversity: newer and more experienced teachers, gender, racial and other diversity, too.

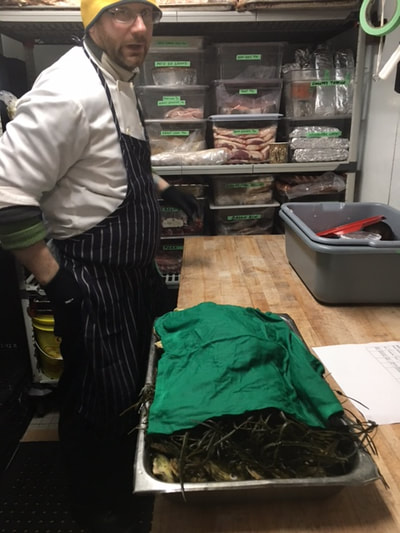

Among themselves, the educators decide who will teach what to whom and when. The flow of the learning is fluid, as different adults in the group may work with different students at different times. Sometimes I am teaching a focused reading lesson with a small group of 5 students while two of my peers are facilitating a science lab with 35-40 other students and our fourth colleague is reviewing a math problem with 8-10 other kids. Another time, each of us has 18-25 students for a 40 minute mapping or fractions or health lesson... and then we switch. And at other times, still, two of us work together with a group of 35-40 students between us.

Sometimes I am teaching math while my colleagues are teaching music, visual art or science, and at other times, they is teaching math while I teaching these other subject. Sometimes one of us is teaching a specified subject, whereas at other times, the learning is so integrated, a visitor would be hard pressed to identify which subject is the focus of the lesson that morning or afternoon.

But instead of 90 hours outside of the work day, this sort of collaboration is built into the very fabric of the way school is structured. All four of us could begin the work one morning before the school day starts, and then two of us could continue the planning while the other two run an hour-long math clinic with the whole group of students. The next day, one of us works with one of them to continue to develop the inquiry plans we've started, while the other works with the other teacher to follow up the math clinic, or writer's workshop, or whatever.

The students, too, get the benefit of four consistent expert learners. They see their teachers as collaborators, communicators and team players, effectively working through problems together.

This serves not only to model the global competencies we hope to engender in students, but also allows students to seek out the support of different mentors from the educator team at different times to serve emergent needs, both academic and social-emotional. No one student is stuck with one teacher with whom they may not have a positive chemistry. (Conversely, each teacher on the team has three colleagues to consult when they face a difficulty with a student or family, as happens from time to time. )

Both in the subject specialty as in the pedagogical skills associated with teaching in general, each educator lends a different perspective that serves to help their colleagues learn and grow, and, as a result, directly benefits the group of students that the team is responsible for.

These teams of 3-4 teachers attend some professional learning together, and some individually. They do some learning on their own as a team, and some with other teams in the school. Oh, and they keep their group of 60-80 students for at least two years, allowing the development of strong relationships with both the students and their families.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed