Serendipitously, my instructional coach had just had a conversation with a colleague of hers about a similar task, and said colleague had shared a link to a short (<20 minutes) documentary about the plight of one group of Syrian refugees in Hungary last fall.

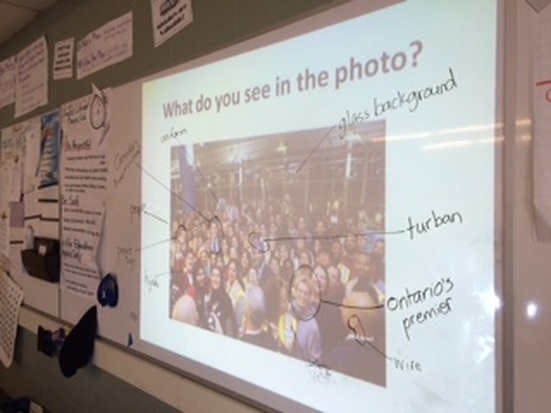

Begin with Vocabulary Development

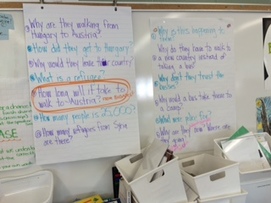

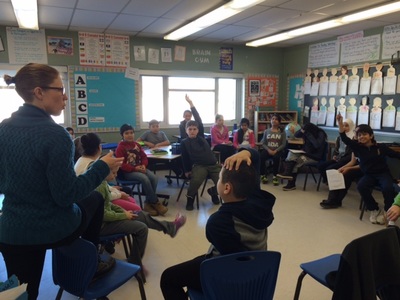

We began with a modified PWIM, to activate students' prior knowledge and build vocabulary for the many students in my class for whom English is not their first language. My instructional coach led the students through an initiating conversation about several photos on the whiteboard, while I labeled the emergent vocabulary in the photos (these "picture dictionaries" were later posted in our virtual classroom on Edmodo, for easy reference by students after the lesson).

At 2:47, we paused the film, and began recording students' questions.

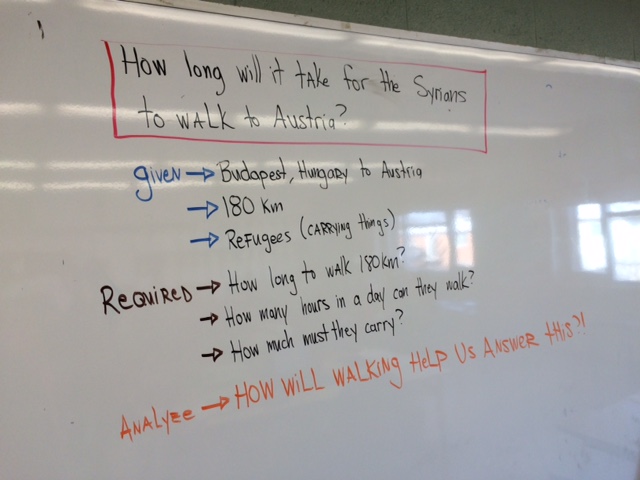

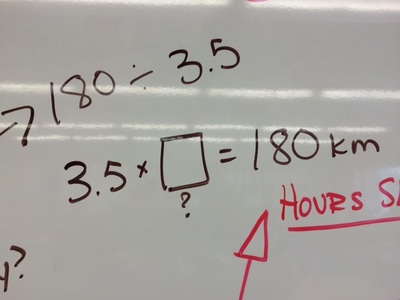

Once we narrowed down the list, and collaboratively (okay, with a little arm-twisting from the teacher -- after all, we wanted a link to math!!) selected the question about how long it might have taken the group of refugees from the film to walk from Hungary to the Austrian border (a distance of 180 km, according to the documentary), we partnered students up and gave them a G.R.A.S.P. organizer to begin thinking about and recording ideas for how they might solve this problem.

While most of the students worked on the "G" ("Given") and "R" ("Required information") sections of the organizer, I took a few students out to another room to work on an alternate problem: One student in particular had been very passionate about saying that he felt 25 000 that the Canadian government had committed to taking in was not a high enough number (he was surprised to learn that some Canadians felt it was "too" high!), as he felt sorry for these people, and believed we should be doing more to help them. I sent him off with another student to consider ways they could help us understand how much 25 000 was, what representations that we could relate to would help us understand that number.

Another student wondered how many refugees there were altogether, fleeing Syria and trying to find a new home. She and a peer went to research this information. (As an aside, they later modified their question, as they discovered "official" numbers of refugees in Canada, in Germany and in other places, and wondered what had become of the rest -- there were still so many, this student pointed out, that were unaccounted for. They are still out researching, and are collaborating in a small group online to prepare a presentation about this data; they will present their findings to the rest of us on Monday.)

Scaffolding for the Many

Because the process of recording so much thinking was so new to many of my students, my instructional coach "coached" them through the first part of preparing to answer the "how long might it take them to walk from Hungary to the Austrian Border?"

Over the weekend, we continued to ponder what information might better help us analyse the problem, and students posted their ideas on Edmodo.

Going for a Walk

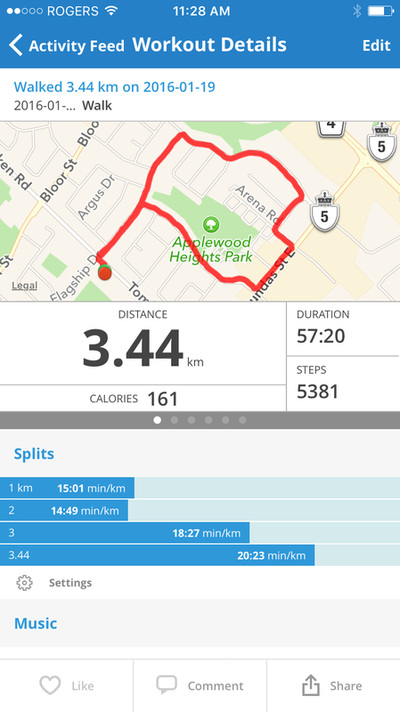

We finally decided that it would be helpful for us to go for an hour-long walk, with backpacks or other heavy-ish items to carry, in a large group, to begin to get a sense of what a typical hour might have been like for the group walking 180 kms from Hungary to Austria.

- How far did we get?

- How are you feeling?

The first ten minutes were filled with excitement and anticipation as we set off to see how much ground we could cover in an hour. Spirits were high, and students chatted animatedly as they walked.

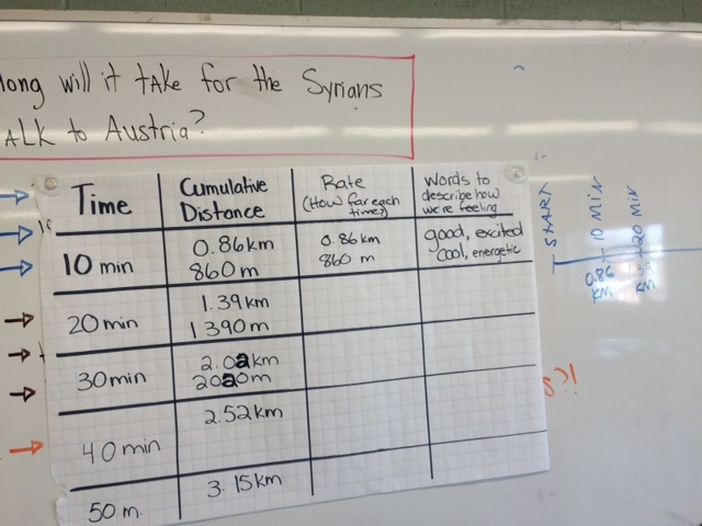

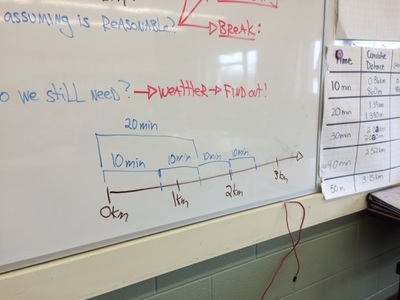

At the ten minute mark, we had walked nearly a km! Students eagerly recorded the data, and began to make predictions about how far we might get in an hour.

It wasn't long, however, before the novelty wore off, and "great" and "fine" (in response to how are you doing? from the the "family" clipboard monitor) turned into "cold", "bored" and "tired". Not one of our subsequent 10-minute segments yielded any distance close to the one we had walked in those first enthusiastic 10 minutes.

The social studies and character ed goals of the lesson were being met!

Now, the Math...

Once back at the school, we began transferring some of our data into a chart which students were asked to complete for homework.

The results, my coach and I soon realised, yielded considerably more math than we had first envisioned: Not only were students converting metric units, but they were being asked to figure out rate and estimate "average" rate (per ten minutes, or per hour, in this case). They were also working through several multi-step parts of the problem to arrive at a solution, and the open-endedness of the numerical possibilities meant that even if every group did the calculations correctly, they could all conceivably arrive at slightly different final answers.

Moving from Analysis to Solving

Then we talked about how this information might be helpful when solving the original problem (basically "how long might it take to walk 180 km"?)

Once students had a sense of what they were trying to find out, we sent them off to work with their partners again, while we circulated. We heavily scaffolded the task for students for whom the existing task was clearly too open, while prompting those who just needed a little push to get to the next stage.

More Math Emerges...

I soon found myself supporting some students in their pre-algebraic thinking, as an argument erupted between two groups about whether the "right" way to find the number of hours it would take was to multiply or divide. (They eventually realised that in fact they were doing the same thing, just coming at it from a different perspective.)

As we wrapped up the math portion of the lesson and prepared to finish showing the documentary that had provoked the initial task, my instructional coach and I reflected on the nebulous nature of true inquiry learning: The time needed to complete a deep and fulsome investigation like this is hard to gauge, and were I less married to my desperate need to micromanage every square inch of my dayplan, I would leave a few "open" periods in my daybook, just to make space for what emerges. This lesson could easily have continued another several periods and yielded rich mathematical discussions in several strands.

It is hard to imagine that a few short years ago I sat in an Equity and Social Justice in the Math Classroom workshop thinking that authentic inquiry through a social justice lens could not be achieved in math, that it was the one subject exempt to the possibility of "real" cross-curriculum links and authentic social justice connections.

I'm here to say I've been converted!

(Interested in the "lesson plan" and a few ppt slides to get the conversation going in YOUR class? Contact me!)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed