Issues of Equity and Social Justice have always been of interest to me. Early on in my career, I participated in a workshop series that challenged my assumptions and helped me to recognize long-held assumptions, as a white, middle class woman. It was there that I was first introduced to Peggy Mcintosh's Invisible Knapsack, as well as my own invisible prejudices. Equity work turned from a fun hobby involving feel-good volunteering on the weekend into uncomfortable but crucial self examination.

As a teacher, as a Christian, as a member of the visible majority, as a woman and as a member of the LGBTQ community, the challenges have only grown over the years, and over the past 12 months, there seems to be an increasing need for me to understand oppression and inclusion on a deeper level.

The introductory matter of a new ETFO resource notes,

Theorists and practitioners alike, think about the goals and practices of global citizenship education in nuanced ways, reflecting what might be referred to as macro-orientations. Some of these orientations emphasize the importance of students developing skills and competencies to be effective participants in the global marketplace. Others emphasize more transformative goals, such as deepening students’ intercultural understandings and/or developing students’ capacities to work for equity and social justice. (from Educating for Global Understanding, pg vi)

Gloria Ladson-Billings, an author whose work seems to keep popping up in this arena, notes global education is of benefit to students in that it promotes critical consciousness. More specifically, students develop a broader social-political consciousness, and eventually they become able to critique the cultural norms, values mores and institutions that produce and maintain social inequities.

That's profound: Imagine if we could somehow compell our future generations to see what so many of us fail to?!

Gloria Ladson-Billings, in her 2008 work on Culturally Relevant Pedagogy, writes, “The first problem teachers confront is believing that successful teaching for poor students of colour is primarily ‘what to do’.”

Instead, she suggests, the problem is very much connected to what we discover at the base of Hume's model of differentiation, above. It rooted in how teachers think: “About the social contexts, about the students, about the curriculum, and about instruction.” (Billings 2008)

I can do the best read-alouds in the world, but if all my books are about straight, white families who live in houses and drive cars, how is Zander who's black and takes the bus and lives with his two moms in an apartment building going to connect to what I am reading, or for that matter, what I say in other subject areas?

Of particular interest was the Implicit Association Test (the work of Mahzarin Banaji), which was posted online. "I've got this licked", I thought, as I clicked the link to take the test.

My results in fact came back fairly typically, and the speed of my associations were not what I would have hoped for someone who considers this her life work in a very practical sense.

So there I was, stretching myself, uncomfortable again. I had spent the year developing a group of multi-lingual grade 3 students into articulate, respectful dialoguers, who could hold an incredible conversation, in English, about topics such as poverty, sexism and racism. I had been invited to be the keynote speaker at a cross-provincial summer conference about this very topic, and I had excitedly shared videos of my students in action with a roomful of passionate, enthusiastic teachers.

Yet here was I, no less prone to stereotypes and prejudices than my non-equity-focused neighbour. It was a disappointing revelation to me.

Ladson-Billings encourages us to explore the experiences that shape our thinking (and subsequently, our behaviour).

Examining my own prejudices is a difficult exercise. I am confined to snippets of child-free time during which to reflect on my classroom and personal experiences. While riding my bike home from work, I reflect on a culturally-focused reading lesson I taught, and consider that writing the actual N-word on the board during a discussion might not have been the best choice, especially for a white, middle class teacher with students of colour in her classroom. While waiting in the noisy upper gallery of the swimming pool where my Grade 3s are learning how to swim for an hour, I consider how to modify my math program to include data that is engages students in thinking about cultural norms while still teaching them how to read and create a tally chart or bar graph. While driving to work one morning, I think back to the faith-based argument I had with my group leader in a course I took some years ago, about teaching for diversity and social justice.

There is rarely enough time to follow one train of thought through to its conclusion, and I am confined to these unsatisfying snippets of insight, these unfinished reflections on how --as a white, middle-aged, Christian, university-educated, LGBTQ woman -- to best teach this stuff in a class full of mainly struggling, culturally diverse 8- and 9-year-olds.

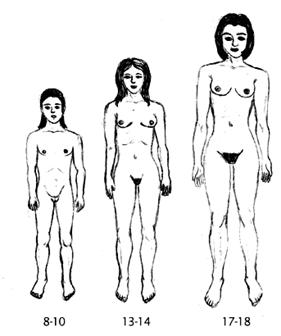

After explaining to us the difference between a cactus and a caucus (in the former, he noted, the pricks are on the OUTside -- ha ha) , Lewis proceeded to convict a room full of 400 educators of the notion that education is the greatest force for good there is. He persuaded us that the school is the centerpiece of creating a new society. He shared some of the work of humanitarian Graca Machel, the repeatedly confirmed, on-the-ground research that children around the world who are in situations of vulnerability just want to go to school. He shared stories of his visits to Africa, and told of the aids orphans and grandmothers, of how in many of the families in that disease and corruption-ravaged wasteland, the oldest sibling is now head of household. He told of an intimate personal moment, during his and Graca’s visit to a small hut in subsaharan Africa, where -- with one sentence -- Graca put aside her big research and mothered a small child, a pre-teen girl with whom no one had yet spoken about the enormous and life-altering changes that were about to come over her in puberty. And he spoke grandly about the atonement needed from the world bank and monetary funds policies.

Nearly a year has passed since that message from Lewis, received in a roomful of educators. Here I am in Argentina now, and although my rhythm this year is a different one, life seems as busy as ever somehow. Yet I find myself reflecting once again upon this problem of how best to teach for social justice… I’m meditating for a while on Ladson-Billings’ proposal, that we need to spend less time on “what to do”, and more time considering our own schemas as teachers, and on the experiences that shape us, and that shape our students.

Many times over the past 12 months I have had the opportunity to consider my own prejudices. I am too prudent to share the specifics on a public blog, but why do I make the assumptions that I do? And more importantly, what other unchecked prejudices do I harbour? Against my colleagues, and against my students from Atlantic Canada? From Carribbean or Asian backgrounds? From the Hindu faith? From single-parent families? And the list goes on… Despite my best efforts to be aware, open and inviting, I find myself surprised -- as in the IAT -- by my own prejudices, subtle though they may be, over and over and over again.

The experiences that shape us include our many interactions with other educators, and with people from backgrounds that are different than our own. These same experiences, then, also shape them. How can we harvest the most produce from such co-experiences?

What impressed me about the above scenario was the way in which the two men handled such a delicate topic. The challenger was not afraid to take it on and speak up, and the challengee did not feel attacked by his challenger (or if he did, he was big enough to let that part of his ego go), and was instead open to considering new ideas, even the idea that he may in fact have been wrong.

Interestingly, I recently came across this quote, which seems fitting:

For social inclusion to resonate, it must provide space for a discussion of oppression and discrimination. Social inclusion has to take its rightful place not along a continuum (from exclusion to inclusion), but as emerging out of a thorough analysis of exclusion. The issue is not “how” to include the excluded but rather “why” people are excluded and “how” to eradicate those conditions and structures of exclusion.

Whereas my quest before tended to revolve around raising awareness in my students of a particular issue, say “racism” or “immigration to Canada” (from the Canadian perspective, whatever that is!), I now am beginning to ask my students more thought-provoking questions when we address social justice issues in class.

I have an increasing awareness that injustice in one area tends to not be an isolated circumstance, that when we dig deeper, we often find co-morbid conditions of equity struggles (for example a young woman of colour may find herself facing the challenge of racism while also fighting for her rights as a female. Because of both of these issues, she may additionally find herself struggling with poverty, which exacerbates pre-existing stereotypes in the minds of others around her). This realization seems at times overwhelming to me: How can I, one teacher with limited life experience, adequately address all the challenges faced by the students in my class, and prepare them to fight the equity and social justice battles of the world in which they are growing up?

Let me return to the Billings quote I shared at the outset of this blog post, the idea about how teachers think: “About the social contexts, about the students, about the curriculum, and about instruction.” Ladson-Billings encourages us to explore the experiences that shape our thinking.

Many experiences have helped to shape my thinking about social justice issues, and indeed, my thinking continues to evolve. What is my role as a perpetrator of injustice in the world, and how have I contributed (and how can I continue to contribute) to a more just society within the constraints of the factory-model public education system in which I work?

I am learning that there is more to equity work than finding and sharing a great picture book with one’s students. Sometimes, there are hard questions to ask, and conflicting ideas to explore.

My pastor, a few weeks ago, when preaching specifically on the topic of social justice, noted that Peace often comes at the cost of great sacrifice.

Sometimes we ourselves must admit that we all harbour prejudices. We must be prepared to face the reality that justice contends with injustice, and that sometimes doing the “right” thing must be considered in the context of the lives it affects within cultures we have little understanding of. In our pluralistic society, conflicting ethics abound. And, as my pastor recently wondered aloud in his Sunday morning sermon, one thing we must consider as we do this important work is this: “Is the division we provoke worth the cause?”

Challenging our assumptions, and moving beyond a “charity” model of social justice is both difficult and rewarding. I am persuaded to continue the quest!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed