With today's Ministry foci on Equity and Well-Being, the 7-year-old assessment policy embodies much of the "how", for educators who understand and implement it effectively. (Good grief, Growing Success 2010 specifically mentions the word "equity" no fewer than 10 times, and includes the following statement: "The policy outlined in this document is designed to move us closer to fairness, transparency, and equity"!)

Ahhh, but there's the rub: Understanding! For some reason, despite pockets of excellence throughout the province, a great deal of misunderstanding about assessment evaluation persists, nearly a decade after the policy's release.

As both an Education Officer with the Ministry of Ed., and a parent of two school-age children, here are three misunderstandings I see most often in my work with Ontario's educators, including school leaders:

1. Feedback should be Provided to Students at the End of each Assignment

Perhaps one of the most powerful strategies within our reach as educators is the development -- ideally with students -- of criteria that describe the desired demonstration of learning, and the provision of feedback to describe learning, so that students know where they need to be, where they are at, and where to go next. When and how to provide said feedback, however, is sometimes a challenge for educators.

The first time Growing Success mentions descriptive feedback is on Page 6, as part of the seven fundamental principles on which the policy is based:

[Teachers] provide ongoing descriptive feedback that is clear, specific, meaningful, and timely to support improved learning and achievement. |

Indeed, on page 28, the policy states,

As part of assessment for learning, teachers provide students with descriptive feedback and coaching for improvement. |

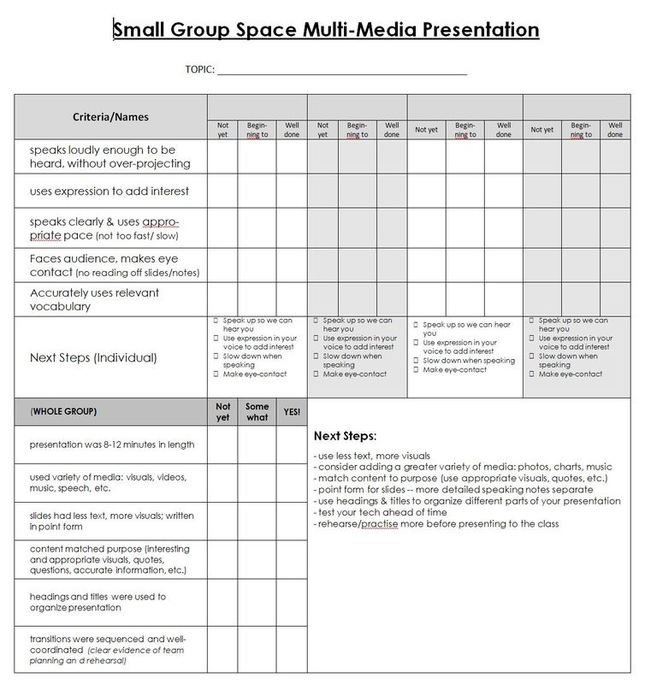

Below is an interactive image, made with Thinglink, to describe where and how descriptive feedback fits into the assessment process:

The timing and nature of descriptive feedback seems obvious to me now, but as a classroom teacher, I will confess that it was the thing I struggled with the most, when it came to assessment. It took me a long time to get over my implicit bias that allowing students to apply the feedback I had given them to a piece of work and resubmit that work for evaluation was "cheating".

It wasn't until I became involved in the early years of theStudent Work Study that I began to realise the true value of feedback, and to use it effectively to improve student learning. (It was also then that I gleaned a better understanding of the distinction between assessment and evaluation!)

Providing feedback at the end of the learning cycle, after an assignment is submitted for evaluation, is in some sense useless. The average student won't read it, and if there is no opportunity to apply the feedback to improve the work, why bother?

2. Group Assignments are Easier to Evaluate

Speaking of reducing my workload, as a classroom teacher in the throes of giant classes, I often turned to group assignments, not just because I believed in the power of collaboration, but also because I hoped for an easier time "marking the work". Alas, as Growing Success points out,

Assignments for evaluation may involve group projects as long as each student’s work within the group project is evaluated independently and assigned an individual mark, as opposed to a common group mark. (Chapter 5/page 39) |

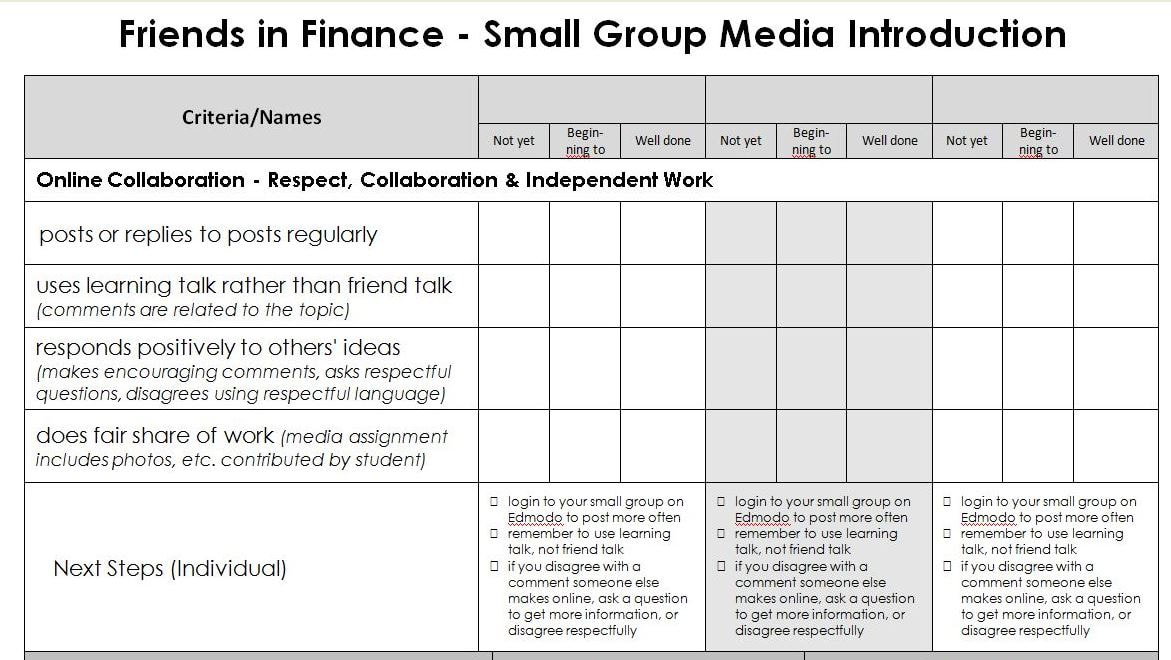

By no means brilliant or perfect examples, nevertheless, a few of my favourite attempts, below...

3. Test in King, at least in Math

A lot of educators (and parents, for that matter), appear to be under the impression that -- especially for subjects like Math -- the most reliable way to discern what students know is by having them write a paper and pencil test.

While tests can be one way to gather data, Growing Success invites us to consider the plethora of ways students may demonstrate their understanding. From page 34:

Teachers can gather information about learning by:

- designing tasks that provide students with a variety of ways to demonstrate their learning;

- observing students as they perform tasks;

- posing questions to help students make their thinking explicit;

- engineering classroom and small-group conversations that encourage students to articulate what they are thinking and further develop their thinking

This was no more clearly demonstrated to me than in a Grade 6 class where I had the pleasure of spending my final year before heading to the Ministry: Dolores (not her real name) was a strong student in mathematics. I knew this because whenever I observed her working on a math problem in class, I could see and hear that she understood the concepts quickly. She used relevant math vocabulary (despite English not being her first language), and reasoned her way through even the toughest problems, often explaining them to her peers by sketching out a diagram to show how something worked.

But when it came to math tests (yes, even in my final year in the classroom, I still resorted to these occasionally!), Dolores froze.

The learning demonstrated on the pencil and paper tests she handed in could at best be summarized as level 2, approaching provincial standard, while all other evidence consistently pointed to a thorough understanding and communication of mathematical concepts (Level 4).

This reinforced for me the messages I had hither-to been preaching as a former school vice principal, board instructional coach, and school level colleague. The truth of differentiated assessment was confirmed for me in the classroom, and I applied this truth to my assessment practice with all students, finding ways for them to show me what they knew and could do.

As pointed out on page 39,

Evidence of student achievement... is collected... from three different sources – observations, conversations, and student products. Using multiple sources of evidence increases the reliability and validity of the evaluation of student learning. |

As a former colleague at the Ministry used to point out, "we're not self-employed, people, and the policy is not invitational!", ie. we don't get to follow it only if if we want to. A better understanding the policy can keep us out of hot water as public educators, and as an added bonus, actually enable us in doing a better job of supporting equity, well-being and academic achievement for all learners.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed