You see, it is our firm belief that simply enforcing hiring quotas, or even developing a staff support group for racialised leaders, or slapping a colour inclusive poster on the wall will not foster a climate of authentic inclusion. While these initiatives are good and necessary, and while they sometimes even come from the right place, they are not enough. In order to truly eradicate racism, the work climate must include an element of intellectual dissonance.

The recent drama in Russia/the Ukraine is a classic example, in my opinion, of western failure when it comes to cultural proficiency.

In the aftermath of the crash, I heard a Canadian speaking with news reporters about the situation overseas. His reasonably well-articulated sentiments echoed those of the president of our neighbours to the south in calling for an immediate cease-fire and cooperation of all parties in order to allow independent investigators to do their work with regards to the commercial airliner that had been recently shot down in that part of the world, tragically killing all on board, including Europeans, Canadians and Americans.

Now, I'm no expert on Russians, but I'm going to go out on a limb here and suggest that any country who chooses to annex -- by force -- bits of a neighbouring country, and then supports (or implies support by not rushing to punish the perpetrators of) the shooting down of a civilian, commercial aircraft is perhaps not playing by the same set of cultural norms as the leaders of the western world would like to think.

This different set of mores was illustrated for me recently by a young Russian with whom I had the opportunity to dine, in my home, with my gay self and my gay girlfriend. After dinner, said Russian (who was well aware of our sexual identity, btw) announced that he would like to go to the Pride Parade... "and stab people"! It's the sort of blatant homophobia I've not heard in Canada for at least two decades. (He later went on -- when I invited him to a further conversation about his aggressive comment -- to denounce anyone in a position of weakness, refer to me as a "fucking retard" who -- being an elementary school teacher and all --brainwashes children. His advice was to "suck it up" and "get over it". Delightful.)

So this young man does not share my idyllic view of how we should all live together in peace and harmony, clearly. (Needless to say, we won't be inviting him over for dinner anymore!!!)

What I am suggesting is that it's a little naive to think that we can just basically tell such a country to play nicely by our western rules of the game, and they will respond cooperatively. (And, by the way, we have to be honest and willing to admit that we ourselves don't always follow our own rules!!)

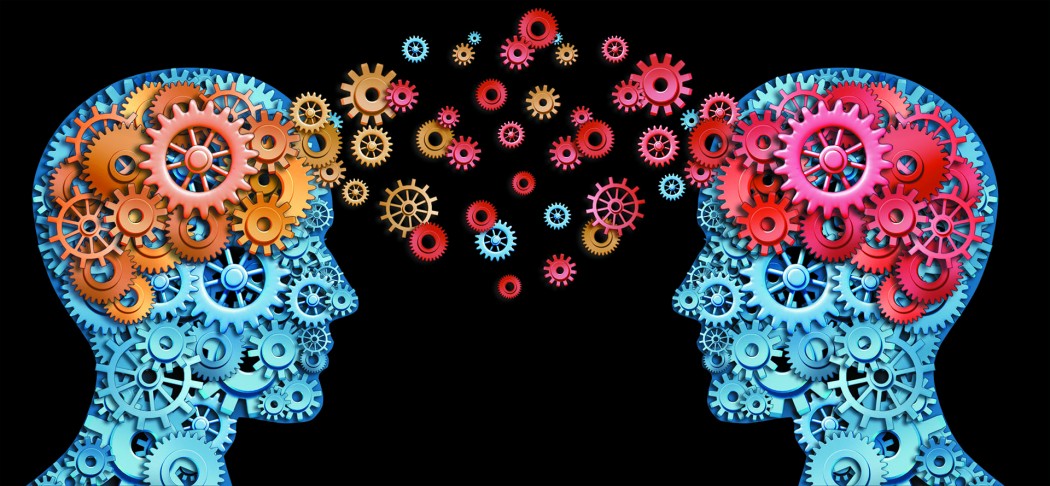

If we want to have a meaningful relationship with a country so apparently different from our own, we need to be committed to finding out what makes that country "tick", so to speak. It's insulting to others to assume that everyone plays by the same rules. If we want to redefine the rules, or rather, create a new, collaborative "world culture", then we first have to hear the voices of all parties at the table. And we need to recognize that it's going to be a noisy, chaotic conversation.

No, "proficiency" in any language, including the language of culture, requires intensive study of and wrestling with the tricky bits of that language. To know a culture, one must learn about its significant historical events, as told from the people of that culture, and as told from a variety of perspectives within the culture. One must learn why the people who leave a country emigrate, and why those who choose to stay do so. One must examine how the "weakest" in the culture's urban and rural societies are treated, and one must consider that culture's relationship with faith, and its stance on the environment.

One might argue that it is impossible, then, to really know a culture, let alone every culture with enough depth to be considered "proficient". I would counter that at the very least, one ought to be open to learning.

And that one might also be willing to admit, "I don't know" as needed.

If we want to make a difference in the long run, and build a global society where people can communicate effectively while honouring the bits of their own culture which -- once scrutinized with a critical, objective-as-possible lens -- they consider worth keeping, then we need in the short run to have real, meaningful and difficult conversations, ones in which we challenge ourselves and each other to look beyond the "cultural mosaic" and into the dark corners of our culture and those of others.

Until we move beyond superficial practice, the world will continue to see missiles rained down on it, civilian airplanes shot out of the skies, women raped, children abused and people from all walks of life mistreated because they don't fit the unchallenged values of the group in power at a particular time and place.

So dig, dig deep, my friends. Cultural proficiency can be achieved, one fine, possibly uncomfortable conversation at a time!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed