In question were two particular pieces of writing students had completed:

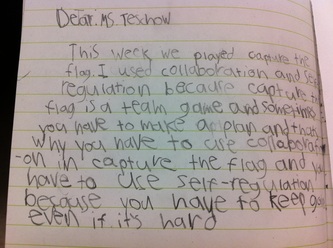

The first was a sort of meta-cognitive exercise, a letter written to me about activities undertaken at school last week, and which Learning Skills students needed to participate effectively in these activities. We had preceded the writing exercise with lots of talk, first a group brainstorming session, and then, the opportunity to discuss both activities and learning skills used, with a partner, before actually writing me the letter.

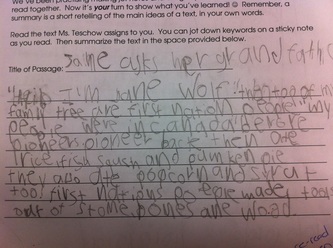

The second writing task involved students summarizing a fairly high-interest passage about which they had some previous schema, but about which we did not really spend any time engaged in oral language immediately preceding the written task. Students were allowed and encouraged to jot down key words on a sticky note as they read the passage, for use when they summarized it afterwards.

I marked the more recent piece, the summary, first, since we’ve been working on summarizing text using key words a lot lately.

Many of the students did surprisingly well, and I was pleased to see that the key word strategy had apparently been working, though some of the usual suspects showed the typical struggles in their work. A few of the students in particular wrote in rather a disorganized fashion, even though they are generally decent readers.

Then I marked the earlier piece of writing, the letter to me that had been preceded by lots of talk.

WOW, was I ever surprised!

Although the tasks were not identical, it seems clear to me that the extensive talk students engaged in before the writing of the letter generated far better quality of writing than the task that was not preceded by an oral language experience.

My reading of ESL literature confirms this supposition, and I am curious to try it out in more similar tasks, to compare the results. I also intend to make more time for oral language in my writing program, and link written tasks to writing where possible.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed