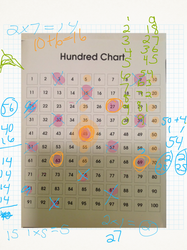

100 Chart in Bamboo Paper App

100 Chart in Bamboo Paper App Among other things, we commiserated about how so many students seem to be struggling in math.

Even with the availability of math manipulatives in the classroom, even with engaging lessons taught on the Smart Board, many of the students seem already by Grade 2 to have major gaps in their mathematical understanding.

And it's not just an "ESL student population" problem. I thought of the Grade 5 student I tutored this past summer, and how surprised I had been at her apparent gaps, too. A native English speaker from an upper-middle class household, this child was an average-to-above-average reader, speaker and writer, but when it came to many mathematical concepts, she panicked, and had already developed a self image that included not being very "good" at math.

Math phobia seems to be at an all-time high, with students as young as Grade 3 proclaiming, “I’m no good at Math”. Or maybe I am just more in tune with this phenomenon because of my own focus on Math last school year. In any case, there seem to be a lot of missing pieces for a lot of students, and, as I become familiar with a wider variety of students’ individual situations, I am beginning to develop a better understanding for why that might be.

I used to think that a major problem with math instruction was that teachers themselves often don’t really understand the math they are supposed to be teaching according to the curriculum. (That certainly applies to me, though in recent years I am becoming more math proficient.)

Increasingly, however, I am beginning to wonder if...

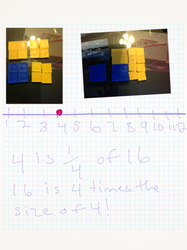

Similarly, students who have had mathematical interactions at home before they arrive at school tend have a far better developed number sense, and are therefore more ready for number-related activities in early primary, which in turn enables them to build a solid foundation for math in the later years.

But, unlike reading to your baby and child, which are now generally accepted and expected things to do as a parent, mathematical conversations are still a rarity in most households.

Case in point: How many toddlers are exposed to a parent who counts aloud with them at the grocery store: “Now we need three potatoes, let’s count them out: 1-2-3, next we need a dozen apples, let’s get 10 red and two green ones, that makes 12”, and so on.

Or, how many parents take time to count the steps each time they climb them with their preschooler? How many “mathematical think alouds” (“Hmmm…. I have 3 forks here, but we have 5 people coming to dinner. That means we need 2 more forks.”) do most children hear by the time they enter school?

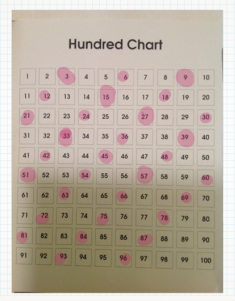

How many parents have access to a hundreds chart at home, and know how to use it to help their children with their math homework?

I suspect the answer to all of these questions is a resounding “not many”.

It does not surprise us that students who come from households where literacy is not a focus struggle with reading and writing, so how can we expect children to come to school ready to learn about math when they have never had the luxury of a mathematical conversation with someone at home in the preceding four years?!

Then, to make matters worse, they arrive in school, largely unprepared for the rigorous math curriculum, and we just jam the latter down their gullets anyway, regardless of what they actually need! It’s true that there is a lot of pressure -- largely due to the current, unwieldy reporting system -- to crank through the curriculum at breakneck speed… but it is not conducive to helping children learn math, in my opinion.

If we could only find a way to get parents on board counting things and noticing patterns with their children long before they arrive in school, and then convince ourselves that it’s okay to teach students rather than curriculum… we might be able to impact positive change.

(In the meantime, we need to deal with our own math phobia if we have it, and take some math courses!!)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed